LUTHER 1527

LUTHER 1527

Moreover, as I have said, even if they discovered certain metaphors, still they cannot prove thereby that it is so in the Supper, and all the toil and care they have expended is merely lost effort. They give me this much credit, however, that in the case of Karlstadt I demolished his touto, and that his was not a sound argument. But if I were to judge between Karlstadt and Zwingli, I would say that Dr. Karlstadt’s touto served this error better than

Zwingli’s metaphor which, however,

has absolutely nothing in it that can disguise the error, because it tries to prove its case purely by unknown, uncertain, and particular propositions—which to every rational mind is ridiculous and ludicrous. -Martin Luther

The Council of Nicaea, 325.

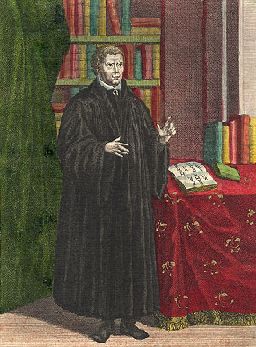

Athanasius the Great.

Athanasius is the theological and ecclesiastical centre, as his senior contemporary Constantine is the political and secular, about which the Nicene age revolves. Both bear the title of the Great; the former with the better right, that his greatness was intellectual and moral, and proved itself in suffering, and through years of warfare against mighty, errors and against the imperial court. Athanasius contra mundum, et mundus contra Athanasium, is a well-known sentiment which strikingly expresses his fearless independence and immovable fidelity to his convictions. He seems to stand an unanswerable contradiction to the catholic maxim of authority: Quod sem per, quod ubique, quod ab omnibus creditum est, and proves that truth is by no means always on the side of the majority, but may often be very unpopular. The solitary Athanasius even in exile, and under the ban of council and emperor, was the bearer of the truth, and, as he was afterwards named, the “father of orthodoxy.”

(Legend) On a martyrs’ day in 313 the bishop Alexander of Alexandria saw a troop of boys imitating the church services in innocent sport, Athanasius playing the part of bishop, and performing baptism by immersion. He caught in this a glimpse of future greatness; took the youth into his care; and appointed him his secretary, and afterwards his archdeacon. Athanasius studied the classics, the Holy Scriptures, and the church fathers, and meantime lived as an ascetic. He already sometimes visited St. Anthony in his solitude.

In the year 325 he accompanied his bishop to the council of Nicaea, and at once distinguished himself there by his zeal and ability in refuting Arianism and vindicating the eternal deity of Christ, and incurred the hatred of this heretical party, which raised so many storms about his life.

In the year 328 he was nominated to the episcopal succession of Alexandria, on the recommendation of the dying Alexander, and by the voice of the people, though not yet of canonical age, and at first disposed to avoid the election by flight; and thus he was raised to the highest ecclesiastical dignity of the East. For the bishop of Alexandria was at the same time metropolitan of Egypt, Libya, and Pentapolis.

But now immediately began the long series of contests with the Arian party, which had obtained influence at the court of Constantine, and had induced the emperor to recall Arius and his adherents from exile. Henceforth the personal fortunes of Athanasius are so inseparably interwoven with the history of the Arian controversy that Nicene and Athanasian are equivalent terms, and the different depositions and restorations of Athanasius denote so many depressions and victories of the Nicene orthodoxy. Five times did the craft and power of his opponents, upon the pretext of all sorts of personal and political offences, but in reality on account of his inexorable opposition to the Arian and Semi-Arian heresy, succeed in deposing and banishing him. The first exile he spent in Treves, the second chiefly in Rome, the third with the monks in the Egyptian desert; and he employed them in the written defence of his righteous cause. Then the Arian party, was distracted, first by internal division, and further by the death of the emperor Constantius (361), who was their chief support. The pagan Julian recalled the banished bishops of both parties, in the hope that they might destroy one another. Thus, Athanasius among them, who was the most downright opposite of the Christian-hating emperor, again received his bishopric. But when, by his energetic and wise administration, he rather restored harmony in his diocese, and sorely injured paganism, which he feared far less than Arianism, and thus frustrated the cunning plan of Julian, the emperor resorted to violence, and banished him as a dangerous disturber of the peace. For the fourth time Athanasius left Alexandria, but calmed his weeping friends with the prophetic words: “Be of good cheer; it is only a cloud, which will soon pass over.” By presence of mind he escaped from an imperial ship on the Nile, which had two hired assassins on board. After Julian’s death in 362 he was again recalled by Jovian. But the next emperor Valens, an Arian, issued in 367 an edict which again banished all the bishops who had been deposed under Constantius and restored by Julian. The aged Athanasius was obliged for the fifth time to leave his beloved flock, and kept himself concealed more than four months in the tomb of his father. Then Valens, boding ill from the enthusiastic adherence of the Alexandrians to their orthodox bishop, repealed the edict.

From this time Athanasius had peace, and still wrote, at a great age, with the vigor of youth, against Apollinarianism. In the year 373 he died, after an administration of nearly forty-six years, but before the conclusion of the Arian war. He had secured by his testimony the final victory of orthodoxy, but, like Moses, was called away from the earthly scene before the goal was reached.

Athanasius, like many great men was very small of stature, somewhat stooping and emaciated by fasting and many troubles, but fair of countenance, with a piercing eye and a personal appearance of great power even over his enemies. His omnipresent activity, his rapid and his mysterious movements, his fearlessness, and his prophetic insight into the future, were attributed by his friends to divine assistance, by his enemies to a league with evil powers. Hence the belief in his magic art. His congregation in Alexandria and the people and monks of Egypt were attached to him through all the vicissitudes of his tempestuous life with equal fidelity and veneration. Gregory Nazianzen begins his enthusiastic panegyric with the words: “When I praise Athanasius, I praise virtue itself, because he combines all virtues in himself.” Constantine the Younger called him “the man of God;” Theodoret, “the great enlightener;” and John of Damascus, the corner-stone of the church of God.”

All this is, indeed, very hyperbolical, after the fashion of degenerate Grecian rhetoric. Athanasius was not free from the faults of his age. But he is, on the whole, one of the purest, most imposing, and most venerable personages in the history of the church; and this judgment will now be almost universally accepted.

He was (and there are few such) a theological and churchly character in magnificent, antique style. He was a man of one mould and one idea, and in this respect one-sided; yet in the best sense, as the same is true of most great men who are borne along with a mighty and comprehensive thought, and subordinate all others to it. So Paul lived and labored for Christ crucified, Gregory VII. for the Roman hierarchy, Luther for the doctrine of justification by faith, Calvin for the idea of the sovereign grace of God. It was the passion and the life-work of Athanasius to vindicate the deity of Christ, which he rightly regarded as the corner-stone of the edifice of the Christian faith, and without which he could conceive no redemption. For this truth he spent all his time and strength; for this he suffered deposition and twenty years of exile; for this he would have been at any moment glad to pour out his blood. For his vindication of this truth he was much hated, much loved, always respected or feared. In the unwavering conviction that he had the right and the protection of God on his side, he constantly disdained to call in the secular power for his ecclesiastical ends, and to degrade himself to an imperial courtier, as his antagonists often did.

Against the Arians he was inflexible, because he believed they hazarded the essence of Christianity itself, and he allowed himself the most invidious and the most contemptuous terms. He calls them polytheists, atheists, Jews, Pharisees, Sadducees, Herodians, spies, worse persecutors than the heathen, liars, dogs, wolves, antichrists, and devils. But he confined himself to spiritual weapons, and never, like his successor Cyril a century later, used nor counselled measures of force. He suffered persecution, but did not practise it; he followed the maxim: Orthodoxy should persuade faith, not force it.

Towards the unessential errors of good men, like those of Marcellus of Ancyra, he was indulgent. Of Origen he spoke with esteem, and with gratitude for his services, while Epiphanius, and even Jerome, delighted to blacken his memory and burn his bones. To the suspicions of the orthodoxy of Basil, whom, by the way, be never personally knew, he gave no ear, but pronounced his liberality a justifiable condescension to the weak. When he found himself compelled to write against Apollinaris, whom he esteemed and loved, he confined himself to the refutation of his error, without the mention of his name. He was more concerned for theological ideas than for words and formulas; even upon the shibboleth homoousios he would not obstinately insist, provided only the great truth of the essential and eternal Godhead of Christ were not sacrificed. At his last appearance in public, as president of the council of Alexandria in 362, he acted as mediator and reconciler of the contending parties, who, notwithstanding all their discord in the use of the terms ousia and hypostasis, were one in the ground-work of their faith.

No one of all the Oriental fathers enjoyed so high consideration in the Western church as Athanasius. His personal sojourn in Rome and Treves, and his knowledge of the Latin tongue, contributed to this effect. He transplanted monasticism to the West. But it was his advocacy of the fundamental doctrine of Christianity that, more than all, gave him his Western reputation. Under his name the Symbolum Quicunque, of much later, and probably of French, origin, has found universal acceptance in the Latin church, and has maintained itself to this day in living use. His name is inseparable from the conflicts and the triumph of the doctrine of the holy Trinity.

As an author, Athanasius is distinguished for theological depth and discrimination, for dialectical skill, and sometimes for fulminating eloquence. He everywhere evinces a triumphant intellectual superiority over his antagonists, and shows himself a veritable malleus haereticorum. He pursues them into all their hiding-places, and refutes all their arguments and their sophisms, but never loses sight of the main point of the controversy, to which he ever returns with renewed force. His views are governed by a strict logical connection; but his stormy fortunes prevented him from composing a large systematic work. Almost all his writings are occasional, wrung from him by circumstances; not a few of them were hastily written in exile.

They may be divided as follows:

1. Apologetic works in defence of Christianity. Among these are the two able and enthusiastic kindred productions of his youth (composed before 325): “A Discourse against the Greeks,” and “On the Incarnation of the Divine Word,)” which he already looked upon as the central idea of the Christian religion.

2. Dogmatic and Controversial works in defence of the Nicene faith; which are at the same time very important to the history of the Arian controversies. Of these the following are directed against Arianism: An Encyclical Letter to all Bishops (written in 341); On the Decrees of the Council of Nicaea (352); On the Opinion of Dionysius of Alexandria (352); An Epistle to the Bishops of Egypt and Libya (356); four Orations against the Arians (358); A Letter to Serapion on the Death of Arius (358 or 359); A History of the Arians to the Monks (between 358 and 360). To these are to be added four Epistles to Serapion on the Deity of the Holy Spirit (358), and two books Against Apollinaris, in defence of the full humanity of Christ (379).

3. Works in his own Personal Defence: An Apology against the Arians (350); an Apology to Constantius (356); an Apology concerning his Flight (De fuga, 357 or 358); and several letters.

4. Exegetical works; especially a Commentary on the Psalms, in which he everywhere finds types and prophecies of Christ and the church, according to the extravagant allegorizing method of the Alexandrian school; and a synopsis or compendium of the Bible. But the genuineness of these unimportant works is by many doubted.

5. Ascetic and Practical works. Chief among these are his “Life of St. Anthony,” composed about 365, or at all events after the death of Anthony, and his “Festal Letters,” which have but recently become known. The Festal Letters give us a glimpse of his pastoral fidelity as bishop, and throw new light also on many of his doctrines, and on the condition of the church in his time. In these letters Athanasius, according to Alexandrian custom, announced annually, at Epiphany, to the clergy and congregations of Egypt, the time of the next Easter, and added edifying observations on passages of Scripture, and timely exhortations. These were read in the churches, during the Easter season, especially on Palm-Sunday. As Athanasius was bishop forty-five years, he would have written that number of Festal Letters, if he had not been several times prevented by flight or sickness. The letters were written in Greek, but soon translated into Syriac, and lay buried for centuries in the dust of a Nitrian cloister, till the research of Protestant Scholarship brought them again to the light. (Schaff, History of the Christian Church, Volume 3NICENE AND POST-NICENE CHRISTIANITY A.D. 311-600 Pages 884-893)

LUTHER 1527

LUTHER 1527