Luther at the Coburg

Luther at the Coburg Castle

Luther’s Letters from Coburg, April 18 to Oct. 4, 1530, in De Wette, IV. 1–182. Melanchthon’s Letters to Luther from Augsburg, in the second volume of the “Corpus Reform.”

Zitzlaff (Archidiaconus in Wittenberg): Luther auf der Koburg, Wittenberg, 1882 (175 pages). Koestlin, M. L., II. 198 sqq.

During the Diet of Augsburg, from April till October, 1530, Luther was an honorable prisoner in the electoral castle of Coburg. From that watch-tower on the frontier of Saxony and Bavaria, he exerted a powerful influence, by his letters, upon Melanchthon and the Lutheran confessors at the Diet. His sojourn there is a striking parallel to his ten months’ sojourn at the Wartburg, and forms the last romantic chapter in his eventful life. He was still under the anathema of the Pope and the ban of the empire, and could not safely appear at Augsburg. Moreover, his prince had reason to fear that by his uncompromising attitude he might hinder rather than promote the work of reconciliation and peace. But he wished to keep him near enough for consultation and advice. A message from Augsburg reached Coburg in about four days.

Luther arrived at Coburg, with the Elector and the Wittenberg divines, on April 15, 1530. In the night of the 22d he was conveyed to the fortified castle on the hill, and ordered to remain there for an indefinite time. No reason was given, but he could easily suspect it. He spent the first day in enjoying the prospect of the country, and examining the prince’s building (Fuerstenbau) which was assigned him. His sitting-room is still shown. “I have the largest apartment, which overlooks the whole fortress, and I have the keys to all the rooms.” He had with him his amanuensis Veit Dietrich, a favorite student, and his nephew Cyriac Kaufmann, a young student from Mansfeld. He let his beard grow again, as he had done on the Wartburg. He was well taken care of at the expense of the Elector, and enjoyed the vacation as well as he could with a heavy load of work and care on his mind. He received more visitors than he liked. About thirty persons were stationed in the castle.

“Dearest Philip,” he wrote to Melanchthon, April 23, “we have at last reached our Sinai; but we shall make a Sion of this Sinai, and here I shall build three tabernacles, one to the Psalms, one to the Prophets, and one to Aesop ... . It is a very attractive place, and just made for study; only your absence grieves me. My whole heart and soul are stirred and incensed against the Turks and Mohammed, when I see this intolerable raging of the Devil. Therefore I shall pray and cry to God, nor rest until I know that my cry is heard in heaven. The sad condition of our German empire distresses you more.” Then he describes to him his residence in the “empire of birds.” In other letters he humorously speaks of the cries of the ravens and jackdaws in the forest, and compares them to a troop of kings and grandees, schoolmen and sophists, holding Diet, sending their mandates through the air, and arranging a crusade against the fields of wheat and barley, hoping for heroic deeds and grand victories. He could hear all the sophists and papists chattering around him from early morning, and was delighted to see how valiantly these knights of the Diet strutted about and wiped their bills, but he hoped that before long they would be spitted on a hedge-stake. He was glad to hear the first nightingale, even as early as April. With such innocent sports of his fancy he tried to chase away the anxious cares which weighed upon him. It is from this retreat that he wrote that charming letter to his boy Hans, describing a beautiful garden full of goodly apples, pears, and plums, and merry children on little horses with golden bridles and silver saddles, and promising him and his playmates a fine fairing if he prayed, and learned his lessons.

Joy and grief, life and death, are closely joined in this changing world. On the 5th of June, Luther received the sad news of the pious death of his father, which occurred at Mansfeld, May 29. When he first heard of his sickness, he wrote to him from Wittenberg, Feb. 15, 1530: “It would be a great joy to me if only you and my mother could come to us. My Kate, and all, pray for it with tears. We would do our best to make you comfortable.” At the report of his end he said to Dietrich, “So my father, too, is dead,” took his Psalter, and retired to his room. On the same day he wrote to Melanchthon that all he was, or possessed, he had received from God through his beloved father.

He suffered much from “buzzing and dizziness” in his head, and a tendency to fainting, so as to be prevented for several weeks from reading and writing. He did not know whether to attribute the illness to the Coburg hospitality, or to his old enemy. He had the same experience at the Wartburg. Dietrich traced it to Satan, since Luther was very careful of his diet.

Nevertheless, he accomplished a great deal of work. As soon as his box of books arrived, he resumed his translation of the Bible, begun on the Wartburg, hoping to finish the Prophets, and dictated to Dietrich a commentary on the first twenty-five Psalms. He also explained his favorite 118th Psalm, and wrote 118:17 on the wall of his room, with the tune for chanting, —

“Non moriar, sed vivam, et narrabo opera Domini.”

By way of mental recreation he translated thirteen of Aesop’s fables, to adapt them for youth and common people, since “they set forth in pleasing colors of fiction excellent lessons of wise and peaceful living among bad people in this wicked world.” He rendered them in the simplest language, and expressed the morals in apt German proverbs.

The Diet at Augsburg occupied his constant attention. He was the power behind the throne. He wrote in May a public “Admonition to the Clergy assembled at the Diet,” reminding them of the chief scandals, warning them against severe measures, lest they provoke a new rebellion, and promising the quiet possession of all their worldly possessions and dignities, if they would only leave the gospel free. He published a series of tracts, as so many rounds of musketry, against Romish errors and abuses.

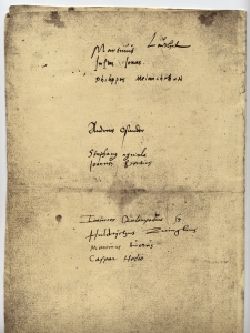

He kept up a lively correspondence with Melanchthon, Jonas, Spalatin, Link, Hausmann, Brenz, Agricola, Weller, Chancellor Brueck, Cardinal Albrecht, the Elector John, the Landgrave Philip, and others, not forgetting his “liebe Kethe, Herr Frau Katherin Lutherin zu Wittenberg.” He dated his letters “from the region of the birds” (ex volucrum regno), “from the Diet of the jackdaws” (ex comitiis Monedu, larum seu Monedulanensibus), or “from the desert” (ex eremo, aus der Einoede). Melanchthon and the Elector kept him informed of the proceedings at Augsburg, asked his advice about every important step, and submitted to him the draught of the Confession. He approved of it, though he would have liked it much stronger. He opposed every compromise in doctrine, and exhorted the confessors to stand by the gospel, without fear of consequences.

His heroic faith, the moving power and crowning glory of his life, shines with wonderful luster in these letters. The greater the danger, the stronger his courage. He devoted his best hours to prayer. His “Ein feste Burg ist unser Gott,” was written before this time, but fitly expresses his fearless trust in God at this important crisis, when Melanchthon trembled. “Let the matter be ever so great,” he wrote to him (June 27), “great also is He who has begun and who conducts it; for it is not our work ... . ‘Cast thy burthen upon the Lord; the Lord is nigh unto all them that call upon Him.’ Does He say that to the wind, or does He throw his words before beasts? ... It is your worldly wisdom that torments you, and not theology. As if you, with your useless cares, could accomplish any thing! What more can the Devil do than strangle us? I conjure you, who in all other matters are so ready to fight, to fight against yourself as your greatest enemy.” In another letter he well describes the difference between himself and his friend in regard to cares and temptations. “In private affairs I am the weaker, you the stronger combatant; but in public affairs it is just the reverse (if, indeed, any contest can be called private which is waged between me and Satan): for you take but small account of your life, while you tremble for the public cause; whereas I am easy and hopeful about the latter, knowing as I do for certain that it is just and true, and the cause of Christ and God Himself. Hence I am as a careless spectator, and unmindful of these threatening and furious papists. If we fall, Christ falls with us, the Ruler of the world. I would rather fall with Christ than stand with the Emperor. Therefore I exhort you, in the name of Christ, not to despise the promises and the comfort of God, who says, ‘Cast all your cares upon the Lord. Be of good cheer, I have overcome the world.’ I know the weakness of our faith; but all the more let us pray, ‘Lord, increase our faith.’ “

In a remarkable letter to Chancellor Brueck (Aug. 5), he expresses his confidence that God can not and will not forsake the cause of the evangelicals, since it is His own cause. “It is His doctrine, it is His Word. Therefore it is certain that He will hear our prayers, yea, He has already prepared His help, for he says, ‘Can a woman forget her sucking child, that she should not have compassion on the son of her womb? Yea, these may forget, yet will not I forget thee” (Isa. 49:15). In the same letter he says, “I have lately seen two wonders: the first, when looking out of the window, I saw the stars of heaven and the whole beautiful vault of God, but no pillars, and yet the heavens did not collapse, and the vault still stands fast. The second wonder: I saw great thick clouds hanging over us, so heavy as to be like unto a great lake, but no ground on which they rested; yet they did not fall on us, but, after greeting us with a gloomy countenance, they passed away, and over them appeared the luminous rainbow ... . Comfort Master Philip and all the rest. May Christ comfort and sustain our gracious Elector. To Christ be all the praise and thanks forever. Amen.”

Urbanus Rhegius, the Reformer of Braunschweig-Lueneburg, on his way from Augsburg to Celle, called on Luther, for the first and last time, and spent a day with him at Coburg. It was “the happiest day” of his life, and made a lasting impression on him, which he thus expressed in a letter: “I judge, no one can hate Luther who knows him. His books reveal his genius; but if you would see him face to face, and hear him speak on divine things with apostolic spirit, you would say, the living reality surpasses the fame. Luther is too great to be judged by every wiseacre. I, too, have written books, but compared with him I am a mere pupil. He is an elect instrument of the Holy Ghost. He is a theologus for the whole world.”

Bucer also paid him a visit at Coburg (Sept. 25), and sought to induce him, if possible, to a more friendly attitude towards the Zwinglians and Strassburgers. He succeeded at least so far as to make him hopeful of a future reconciliation. It was the beginning of those union efforts which resulted in the Wittenburg Concordia, but failed at last. Bucer received the impression from this visit, that Luther was a man “who truly feared God, and sought sincerely the glory of God.”

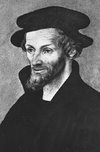

There can be no doubt about this. Luther feared God, and nothing else. He sought the glory of Christ, and cared nothing for the riches and pleasures of the world. At Coburg, Luther was in the full vigor of manhood, — forty-six years of age, — and at the height of his fame and power. With the Augsburg Confession his work was substantially completed. His followers were now an organized church with a confession of faith, a form of worship and government, and no longer dependent upon his personal efforts. He lived and labored fifteen years longer, completing the translation of the Bible, — the greatest work of his life, preaching, teaching, and writing; but his physical strength began to decline, his infirmities increased, he often complained of lassitude and uselessness, and longed for rest after his herculean labors. Some of his later acts, as the unfortunate complicity with the bigamy affair of Philip of Hesse, and his furious attacks upon Papists and Sacramentarians, obscured his fame, and only remind us of the imperfections which adhere to the greatest and best of men.

Here, therefore, is the proper place to attempt an estimate of his public character, and services to the church and the world.

HISTORY OF THE CHRISTIAN CHURCH Schaff Volume 7 MODERN CHRISTIANITY THE GERMAN REFORMATION (Pages 723-729)